Luminaries: The MLK of India

Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar’s place in the annals of Indian history as a champion of the oppressed is no less significant than that of Martin Luther King Jr. in American history.

(Photos: Wikimedia Commons)

Like Martin Luther King Jr., who had to be born black to experience the horrors of racism, Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar experienced abject degradation and debilitating discrimination simply on account of being born an “untouchable.” His caste—Dalit— was considered the lowliest in India’s longstanding caste system. These supposed pariahs were relegated to the outskirts of society, denied access to establishment institutions, and prohibited from physical proximity, much less contact, with other castes.

Born on April 14, 1891, Ambedkar endured the stranglehold of untouchability and dehumanizing discrimination for most of his life. Like others of his lot, he was required to bring his own water tumbler and straw mat to school to prevent the objects he had used from polluting the “higher” caste children and school staff. Such caste-based segregation continued throughout his college and work life, with dorms and renters denying him places to live in and offices to work from.

It was nothing short of miraculous how Ambedkar overcame his caste constraints becoming the first untouchable to be admitted to the University of Bombay’s Elphinstone College. Shocking the privileged class, he went even further—to earn doctorates in Economics from the prestigious Columbia University and the London School of Economics.

His academic work included an impressive analysis of the Indian economy from ancient to colonial times, the British manipulation of the rupee, and the negative impact of exploitative colonization and societal inequity. The latter led him to present a paper on “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development” at a seminar in America. This was among his earliest analyses of caste structuring and its role in cementing and perpetuating discrimination.

His academic work included an impressive analysis of the Indian economy from ancient to colonial times, the British manipulation of the rupee, and the negative impact of exploitative colonization and societal inequity. The latter led him to present a paper on “Castes in India: Their Mechanism, Genesis and Development” at a seminar in America. This was among his earliest analyses of caste structuring and its role in cementing and perpetuating discrimination.

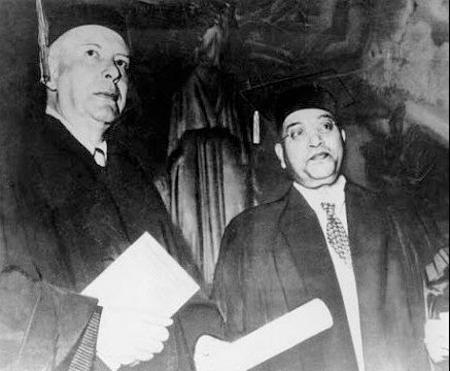

[Right] Dr. B.R. Ambedkar with Wallace Stevens at Columbia University where he earned an honorary doctorate for his service as “a great social reformer and valiant upholder of human rights.” (1952) (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

Ambedkar’s time at Columbia exposed him to John Dewey and his work on democracy, which shaped his own understanding of democratic tenets. Incredibly equipped with a multifaceted intellect, while enrolled at the London School of Economics, he simultaneously trained in law at Gray’s Inn, London. This enabled him to eventually practice law on his return to India, while also teaching economics and finance as a college professor.

Despite his academic brilliance and financial support from a generous lifelong Parsi friend, and enlightened royal patrons like Maharaja Gaikwad of Baroda and Shahu Maharaj of Kolhapur, access to housing, office spaces, and other public facilities continued to be a problem on account of his caste. In his professional career as an accountant and a lawyer, he faced the same inhumane discrimination when clients resisted hiring and dealing with an untouchable. These constraints made it challenging for Ambedkar to provide for his family. His health suffered along with that of his wife and children, causing the couple to endure the loss of four of his five children.

Ambedkar turned the heartache and outrage over his humiliation into activism. The more hurdles his caste placed before him, the greater became his desire to cope and succeed. He soon rose to become a forceful voice for his people and a nationally prominent champion against caste discrimination. Like King, he led marches to protest and breach the barriers preventing untouchables from entering temples, accessing public wells and water tanks, schooling, dwelling, commuting, and other facilities.

Like Gandhi, he resorted to satyagraha (soul force or peaceful protest) to advance his cause. At the same time, he was not afraid to challenge and deride Gandhi’s benign approach to reforming Hindu society. He didn’t see any enduring value in Gandhi’s bold gestures of embracing untouchables as “Harijan” (“God’s people”) and living amongst them in defiance of Hindu taboos.

Rejecting Gandhi’s reformist approach as gradualist, archaic, top-down, patronizing, and not rights-centered, Ambedkar openly broke ranks with Gandhi and the Brahmin elite. He became a vocal critic of Manusmriti (Laws of Manu), the ancient Hindu text, for its ideology of justifying the caste system and perpetuating discrimination and untouchability. In a powerful display of mass awakening and mobilization, he, along with thousands of his followers, publicly burnt copies of Manusmriti.

Rejecting Gandhi’s reformist approach as gradualist, archaic, top-down, patronizing, and not rights-centered, Ambedkar openly broke ranks with Gandhi and the Brahmin elite. He became a vocal critic of Manusmriti (Laws of Manu), the ancient Hindu text, for its ideology of justifying the caste system and perpetuating discrimination and untouchability. In a powerful display of mass awakening and mobilization, he, along with thousands of his followers, publicly burnt copies of Manusmriti.

[Left] Dr. Ambedkar was an eminent Indian jurist, economist, political reformist, and civilrights leader. (Photo: Wikimedia Commons)

His effective representation and mobilization of the underprivileged, along with his intellectual accomplishments, were not lost on his Indian counterparts fighting to free India or on the British colonial rulers seeking to mollify “natives.” Sensing his prominence, the British invited Ambedkar to testify before the Southborough Committee tasked with preparing the Government of India Act 1919. In that hearing, he effectively argued for creating separate electorates and reservations for untouchables and other minority religious communities. His legal acumen won additional wide acclaim after he successfully defended three non-Brahmins who were sued for libel after accusing the Brahmin community of ruining India. That landmark victory remains a turning point in India’s understanding of caste prejudice and injustices.

His continued exposure of caste oppressions through informed editorial opinions and provocative articles, along with his success in organizing his community, made Ambedkar their undeniable leader, giving him the required clout to speak and negotiate on their behalf throughout India’s long struggle for freedom. Unsurprisingly, it led to his being chosen to head the Committee entrusted with drafting the Constitution of India. Free India acknowledged his indispensability when its first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, inducted him to serve as Law and Justice Minister in his maiden Cabinet.

Just prior to his death in 1956, Ambedkar’s longstanding distrust of Hinduism’s inequities, and the pain and humiliation he had personally suffered from caste biases, led him to embrace Buddhism, whose non-discriminatory humanism he found compelling. His public renouncing of the faith of his birth was not done in isolation. It was accompanied by mass conversions of thousands who shared similar caste-based deprivations.

While Gandhi has been called the Mahatma or the Great Soul, what other than a similar greatness and soul force residing within an untouchable child could have driven him to unparalleled heights and to have his accomplishments lead to his recognition as the Father of the Indian Constitution. A grateful India awarded Bharat Ratna, India’s highest civilian award, to him. That it came posthumously is more a reflection of bureaucratic sloth than of any flaw in this extraordinary man.

Neera Kuckreja Sohoni holds a master’s degree in history and a PhD in economics. Her articles have been published in leading newspapers in the U.S. and India.

Enjoyed reading Khabar magazine? Subscribe to Khabar and get a full digital copy of this Indian-American community magazine.

blog comments powered by Disqus