Americana: Negro Spirituals

In 1892, the famed Czech composer Antonin Dvorˇák arrived in the United States to begin a three year stint as director of our National Conservatory of Music. His goal was to encourage Americans to develop their own unique style of music. After studying the musical landscape of a country that was barely 100 years removed from the American Revolution, and less than 40 years from the Civil War, he offered the following:

…inspiration for truly national music might be derived from the Negro melodies. I was led to take this view partly by the fact that the so-called plantation songs are indeed the most striking and appealing melodies that have yet been found on this side of the water, but largely by the observation that this seems to be recognized, though often unconsciously, by most Americans…The most potent as well as most beautiful among them according to my estimation, are certain of the so-called plantation melodies and slave songs, all of which are distinguished by unusual and subtle harmonies, the like of which I have found in no other songs but those of old Scotland and Ireland.

Those plantation melodies and slaves songs, many of which are now part of a classification known as “Negro Spirituals,” never became our “national music.” But to then dismiss their influence on American culture and history is an oversight, and a severe one at that. Need proof? Some of the songs composed by these African-American slaves are now found in hymnals and are sung in Christian churches throughout the land. The greatest rock and roll singer in the history of the world—Elvis Presley—was often cited as “returning to his roots” when he sang variations of the musical genre. Over the years, the Negro Spiritual gave birth to other forms, including Blues, Gospel, and Jazz. During the Civil Rights movements of the 1960s, these songs were sung by black and white Americans as they marched on the dusty roads of the South, seeking justice for a race of people who because of the color of their skin, could not find work, enjoy a sandwich at a downtown lunchroom counter, sip water at a public fountain, or sit in the front-row of a city bus. If Dvorˇák was right in his 1892 assertion that most Americans were “unconscious” of the beauty and influence of the hymns, how much truer his words are now, 120 years later. Let us chisel away at this oversight.

The story of the Negro Spirituals begins with the horrors of slavery. Historians quibble about precise numbers, but most agree that at least 100,000 men and women were forcibly removed from their homes in Africa, packed into the cargo areas of overcrowded boats, and then shackled into position for the long and miserable voyage to America. If they survived the journey, they were then sold at “slave auctions” in cities such as Charleston and Savannah, herded to plantations, and forced to live out their lives in the cotton, tobacco, and rice fields of the American South. Slaves first arrived in this country at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1619. It was not until the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 that slavery was outlawed.

Plantation owners, the “masters,” saw themselves as “God-fearing” men. As such, they made sure their slaves learned the Bible. In truth, the slaves learned select portions of the Bible. Plantation owners didn’t want the more “controversial” gospel verses read to their slaves, particularly those thorny passages noting that we are “all equal before the eyes of the Lord.” Instead, plantation owners would encourage ministers to twist and teach the verses of the Bible in a way that benefited the status quo.

Music historians agree that these three influences— the slave’s native African culture, the anger of the oppressed, and the influences of the Christian religion— were the major influences to the creation of the Negro Spirituals. But let’s shove aside this clinical summary, and hear the words of a woman who was of the era. “Aunty,” in response to the question, “Who composed the Negro Spirituals?” said the following:

“When Mass’r Jesus He walk de earth, when He feel tired He sit a-restin on Jacob’s well and make up dese yer spirituals for His people.”

Such powerful words of faith! Aunty, and the other slaves, instead of understandably turning away from God, reached out, and kept reaching out, and when then couldn’t reach any more, they did anyway. Such convictions are in the music and lyrics of the Negro Spirituals.

On occasions, a white minister might lead the service for the slaves, but more likely, a respected member of the slave community would lead the gathering. Since slaves were not allowed to read nor write, the standard resources of Christian worship—Bibles and hymn books—were not available. Practically, the worship leader might sing a short song verse, one that the people could remember and repeat. Then, the leader would add another short verse, and the people would follow his lead. This highly responsive style, replete with exuberance and creativity in movement and lyrics, is the form of the Negro Spiritual. The difference between a Negro Spiritual and a white person’s Christian hymn is the same as the gap between a Bollywood dance and a European waltz.

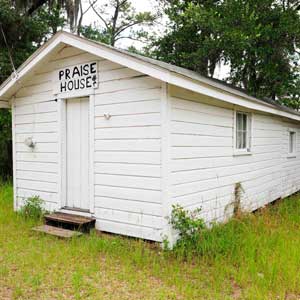

Slaves would gather for their community meetings and worship in places known as “Praise Houses.” Plantation owners, naturally, did not want to worship side-by-side with their slaves, so they built these tiny buildings for their human chattel. It is here that Aunty and her generations sang their songs, titles such as “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child,” “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” “Let Us Break Bread Together on our Knees,” and the famous, “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot.”

The Emancipation Proclamation, by ending slavery, reduced the social pressures and structures that led to the genre. As the now-free blacks moved northward away from the plantations of the Carolinas and Georgia, they took their music with them. Over time, changes occurred in the structures of the verses and lyrics, changes significant enough for musical experts to define the subtle mutations as “gospel music.”

The Negro Spiritual’s finest hour on the national stage was during the Civil Rights movement of the 1960s. As a young boy I’d watch the evening news, and hear and see accounts of peaceful civil rights marchers, seeking nothing more than equal rights for blacks, attacked on their marches through the South. As they marched, they sang the songs of the slaves, including “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” and “We Shall Overcome.” The latter, while written in the 1940s, was based on the 1900 song, “I Shall Overcome Some Day.” The first few verses of the most recent version are as follows:

We shall overcome, we shall overcome,

We shall overcome someday;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe,

We shall overcome someday.

The Lord will see us through, The Lord will see us through,

The Lord will see us through someday;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe,

We shall overcome someday.

We're on to victory, We're on to victory,

We're on to victory someday;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe,

We're on to victory someday.

We'll walk hand in hand, we'll walk hand in hand,

We'll walk hand in hand someday;

Oh, deep in my heart, I do believe,

We'll walk hand in hand someday.

Many famous American singers have performed this song, but to me, all renditions pale when compared to the recording by the great singer, Mahalia Jackson. Search YouTube [or see below this article], find her late 1960s live performance, and feel the very heart and soul of the Negro Spiritual.

If Dvorˇák was right in his long ago assessment that most Americans were “unconscious” of the strains of the Negro Spiritual in American music and culture, how much truer his thoughts are today. Earlier this summer, with a mind to seeing a Praise House, I traveled to the coastal areas of Georgia and South Carolina. I knew from my readings that age, indifference, and prosperity have taken their toll on nearly all of these historic buildings. I was therefore not surprised when I heard, “No, that Praise House is gone,” several times, before finding one not too far from Savannah. I parked my car and slowly walked toward the small clapboard structure, the birthplace of the Negro Spiritual.

Americana is a monthly column highlighting the cultural and historical nuances of this land through the rich story-telling of columnist Bill Fitzpatrick, author of the books, Bottoms Up, America and Destination: India, Destiny: Unknown.

Website Bonus Feature

Video:

"MAHALIA JACKSON Live late 1960's We shall overcome"

Enjoyed reading Khabar magazine? Subscribe to Khabar and get a full digital copy of this Indian-American community magazine.

blog comments powered by Disqus