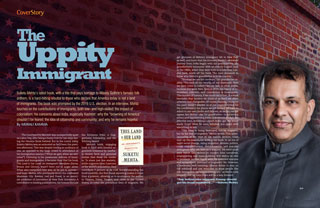

The Uppity Immigrant

|

Suketu Mehta’s latest book, with a title that pays homage to Woody Guthrie’s famous folk anthem, is a hard-hitting rebuttal to those who declare that America today is not a land of immigrants. The book was prompted by the 2016 U.S. election. In an interview, Mehta touches on the contributions of immigrants, both low- and high-skilled; the impact of colonialism; his concerns about India, especially Kashmir; why the “browning of America” shouldn’t be feared; the idea of citizenship and community; and why he remains hopeful. |

The Courtyard by Marriott was unexpectedly quiet on Labor Day, after being a buzzy hub for two days during the Decatur Book Festival. But in the comfy lobby, Suketu Mehta was as animated as he’d been the previous afternoon. This was despite having an audience of one, as opposed to the large crowd in attendance at his immigration session (“What we gain when we welcome”). Listening to his passionate defense of immigrants and immigration, it became clear that his book, This Land Is Our Land: An Immigrant’s Manifesto (Farrar, Straus and Giroux), wasn’t born out of anger alone. What also compelled him was, as he put it, sorrow— and hope. Mehta, who previously wrote the celebrated Maximum City: Bombay Lost and Found, is an associate professor of journalism at New York University. A contributor to leading publications, his honors include the Kiriyama Prize, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and the Whiting Award.

(Below) AJC reporter Jeremy Redmon (left) was the moderator for an immigration panel featuring authors Suketu Mehta and Aleksander Hemon (right) at the Decatur Book Festival.

Mehta’s brisk, engaging book is filled with forceful arguments bolstered by carefully chosen facts and personal stories that draw the reader in. To share just one statistic, while migrants form 3 percent of the world’s population, they contribute 9 percent of its GDP. Notwithstanding the book’s subtitle, the first-hand reporting makes it more than a polemic, allowing us to accompany the author to Tijuana, Dubai, Tangier, and cities in the United States, to enter the precarious lives of migrants. We get glimpses of Mehta’s immigrant life in New York as well, and learn that his itinerant family’s westward journey from India began with his grandparents. His grandfather’s encounter with an elderly English man in the 1980s, when they were both in a suburban London park, starts off the book. The man demands to know why Mehta’s grandfather is in his country.

“Because we are the creditors,” the grandfather replies. “You took all our wealth, all our diamonds. Now we have come to collect.” We are here, in other words, because you were there. Even in 2019, the legacy of colonialism, colorism, and corporatism is inescapable. This burden of history, if we could call it that, is a stark reminder that borders we think of as fixed are often arbitrary and changeable. Of course, blaming others (or the past) doesn’t absolve us of our responsibilities for the conditions in the places we left behind. We have to admit to our own faults and failures, as Mehta readily agrees. But Mehta—like his grandfather—is not wrong either, and his blistering prose and rhetorical style are effective here, delivering a punch in the gut. You won’t easily forget what he says, whether you agree with everything or not.

“The West is being destroyed, not by migrants, but by the fear of migrants,” Mehta writes. This quote, appearing at the start of the middle section, could sum up his reasons for writing the book. In an era of rapid social change, rising migration, divisive politics, crude majoritarianism, disinformation, and populist strongmen who use hate as a weapon, we need more sane voices like Mehta’s to counter false narratives, scapegoating, and mass hysteria. Will Mehta be able to persuade nativist bigots with his reasoned analysis and sympathetic portrayal of migrants? No. However, if moderate, well-meaning citizens refuse to stay on the sidelines and pay attention to what people like this immigrant—or “uppity immigrant,” as Mehta calls himself—tell us, then there will be a way forward.

“Any Indian who supports Trump should get his head examined …”

—Suketu Mehta

Q&A

You once wrote that if India lay south of the U.S. border, “talk show hosts would rail against us just as they do against Mexicans.” But despite everything that’s happened in the last few years, I think Indian-Americans tend to be complacent, perhaps because they are economically successful.

The good news is that Indian-Americans are the most Democratic of all Asian American groups. In the presidential election, only 14 percent of Indians voted for Trump. In the mid-terms, even fewer Indian-Americans voted Republican. The same people who will blindly support Modi will also dislike Trump. The ones who vote Republican tend to vote not on the basis of race, but for economic reasons—doctors, for example, think that they will have lower taxes. Indian-Americans are beginning to realize that Trump is a threat

to all of us.

An H-1B visa holder I spoke to recently is an engineer from Hyderabad, and he has a job in D.C.—but he now wants to go to Canada because his wife is on an H-2B visa and cannot work here. The climate towards all immigrants, not just Mexicans, is really threatening and Indian-Americans are seeing that. So I think in the next election you will see even fewer Indian-Americans voting for Trump. He is alienating not just Latinos, but all people of color.

A lot of Indian-Americans think that high-skilled people should be given preference. But I think they are being short-sighted, right?

Yes. There are two wings pushing immigration policy in the Trump administration. Jared Kushner wants a Canadian-style, points-based system where only high-skilled people come in—because he realizes this country is doomed without immigrants. Can you imagine Silicon Valley without any Indians or Chinese? Can you imagine any American hospital without Indian doctors? They need us. We should stop apologizing. They need us.

But there’s also the Steven Miller wing of the administration which is downright racist. They don’t want non-white people. Period. They are openly racist. The president is openly racist. He doesn’t like Indians. It was farcical—these Indian real estate developers “wishing him” after the election. And they are putting up these Trump-branded apartments in Pune. All he knows about India is to say, “I love the beautiful Bollywood actresses!” Any Indian who supports Trump should get his head examined, because this man is a danger to all of us. There are people in his administration who hate immigrants, particularly non-white immigrants. They want America to return to before 1965, which was when the quota on Asians was lifted.

It’s great that you brought up that point. Yesterday, too, you made some strong economic arguments for immigration. And not only economic; immigrants are more family-oriented, law-abiding, and more religious in some ways. But how do you win the economic argument when it’s really about racial and cultural identity?

There are some Indians who say, it’s good, let them keep the Mexicans out, we are not like that, we have skills, we are better than the Mexicans. Well, if you let them go after the Mexicans first, then they will come after the Indians next. This country needs low-skilled labor as much as it needs high-skilled labor. You have to eat. The Indian doctor has to eat. The Indian doctor is not going to go in the farms and grow peaches and vegetables. Latinos will—at least initially, until their children, too, get educated.

And the population is aging, as you mentioned yesterday. They need aides and other health care workers as they grow older.

Yes. So the numbers are very solidly on the pro-immigration side. There’s just no doubt about it. There is no serious economist who says immigration is bad for the economy. But it’s more than numbers. It’s about culture, it’s a certain narrative about immigration. So when the president says, these people are bad, they are coming here to commit crimes, look at these gangs, and they are raping our women, it’s a very emotional argument. So it has to be countered by other emotional arguments, like the story I told of the pinky kisses [in Friendship Park, along the U.S.-Mexico border, where an outer perimeter fence only allows the touching of fingers]. There were people crying in the

audience. Most Americans, I believe, are good people; they are not out-and-out racists. They are amenable to persuasion. And I am talking about working class whites, even in Southern states like Georgia.

When you get to know people, it’s different.

All these studies have shown that when people know immigrants individually, then they start drawing distinctions. They’ll say, well, I don’t like illegal immigrants, but there’s this one Mexican guy I know, and he’s got this taqueria in my town; he works really hard and his whole family works there. No, he’s different.

You’ll find the same thing in India—Hindus who hate Muslims. Like my cousin, a lawyer in Bharuch. But every evening he goes for a walk with his Muslim best friend around the town. Because I’ve studied ethnic violence in India, I can see how Americans, too, are individually multiple. They’re able to compartmentalize their minds. My job as a storyteller is to get to the part that’s open to emotion with a story like the story of these mothers and sons.

So is that why you went to Mexico and Morocco and other places, to get those stories which you think will strengthen your argument?

First, you have to get them through the heart. That’s where this story is coming. But it can’t be left at that alone. Because then they’ll say this story is different. Then it has to go up to the head, and that’s where the numbers come in, where I spent a lot of time. I have 50 pages of footnotes in my book, gathering the numbers that make the case that a story is not an isolated anecdote. And then once the head and heart have been joined like that, I come to the argument, which is that greater immigration is good for everyone.

I hope they get the argument. But I think what happens is that a lot of whites see their cultural and racial dominance threatened. If you are secure, you can be magnanimous and say, oh, you can come in. Reagan was like that. But now they are seeing the demographic shifts. That’s only going to get worse. Then it becomes harder to persuade them, becomes harder to say, hey, you have to lose some power in order to accept us.

So my response to such fears is, tough shit! You didn’t give us a choice when you got there; now to a certain extent, you don’t have a choice. They are going to keep coming. You will lose white hegemony, that’s a given. By the year 2044, this country is a majority-minority nation. In the big cities, you already have non-white mayors. No, the whites don’t have a God-given right to America for all time. However, they shouldn’t be afraid of losing power. They will never lose complete power. And the whole notion of whiteness is itself changing.

Because of intermarriage.

I have statistics in my book about intermarriage. It’s accelerating dramatically. And that, I believe, is a hopeful sign for the whole race. You know, we have

always intermarried. This concept of white … all these Latinos, for example, who are all white for all purposes, except they happen to have a Spanish last

name. Who’s white and who’s black? There are so

many Indians who have married whites. So are their children Indian or white? The whole concept of race

is increasingly absurd.

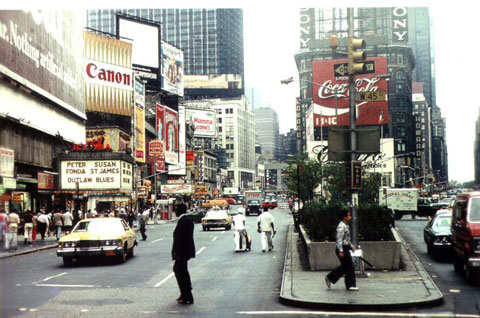

(Left) Midtown Manhattan in 1977, the year Mehta immigrated with his family. One way to think of American exceptionalism is that “it’s a country made up of all the other countries,” he notes.

In your book, you talk about how New York changed. When you came here in the ’70s, it was very different. You’ve seen how it became more multicultural and more accepting.

It’s a good thing when people mix, it’s a good thing when you have heterogeneity. In New York where I come from—I’ve now lived there for 42 years— two out of three New Yorkers are immigrants or their children. It’s a majority-minority city. And it’s flourishing. It’s never been safer, it’s never been richer. That’s true of all cities, and New York realizes that immigration works for the city. It has the most talented immigrants, the most hard-working immigrants from all over the world—and that’s why it’s doing well.

(Right) Mehta, who worked on the screenplay of Mission Kashmir, says that what’s happening in Kashmir is “horrifying” and what’s happening in India now is “alarming.”

You wrote the screenplay for Mission Kashmir. What do you think of what’s happening in Kashmir today? Do you see parallels? Does your book have relevance to what’s going on today?

Very much so. I was one of four screenwriters for Mission Kashmir. I did that mostly so I could research the Bollywood chapter of my book [Maximum City]. I don’t necessarily agree with the point of view of the film. What’s happening now in Kashmir is horrifying. The Kashmiri people have been victims now for decades, and they are being further victimized. It’s a huge mess, not just for the Kashmiris, but for India and Pakistan. We have been constantly on the brink of war over this one issue. It didn’t originate with India and Pakistan or with Hindus and Muslims. It originated with the British. When they left, after having pillaged the country for two hundred years, they left with a final affliction, with lousy map-making. They brought down this

barrister from London, Radcliffe, and gave him five weeks to draw two lines down a map. Those lines are terrible lines, they make no sense.

Every Indian is part Muslim … you and I are part Muslim. We have an intimate knowledge of Muslim culture, of food, and every Indian Muslim is also part Hindu and part Christian and part Sikh. That’s what makes us Indian, basically. And so, when we hate Muslims, we are hating a part of ourselves. Every Indian bigot, every Hindutva bigot that I have met—and I have met a lot of them—hates that part of themselves that is Muslim. And so, if we alienate 200 million Indian Muslims, which is the second biggest Muslim country in the world, if we think of them as the other, then there’s going to be a civil war. What’s happening now in India is deeply, deeply alarming. I’ve never seen it so bad.

You made some strong arguments about how colonialism destroyed these countries. That’s why migrants are coming here. Now the excesses of corporate capitalism are doing the same thing. But Indians are often accused of pointing fingers. Where do we take the responsibility? I mean, India is notorious for poor governance, corruption, and the divisions that you were just talking about.

So what I say in my book is, not everything we are going through can be ascribed to the colonizers. I simply say that some of it is our own damn fault. And right now, this anti-colonialism is being used in the service of Hindutva ideology. There’s a wholesale revision of Indian history textbooks … it’s as corrupt, as intellectually dishonest as British colonial history. In some cases, it is even worse. They come up with these crackpot ideas, like everything began in the Vedas, the Aryans originated in India—such utter nonsense, which is now being printed in the official syllabi of Indian textbooks.

Yes, we are a democracy, but it certainly hasn’t been a democracy that has worked for a majority of the people. When I see children on the streets of cities, taught to beg before they learn to walk, it breaks my heart. That’s why I’ve started a children’s NGO called the Maximum Child Trust. It’s a legal defense fund for Indian children, and I’m going to litigate and sue the government to live up to its statutory obligations towards Indian children. I still have hopes for Indian democracy. For 5,000 years, the upper castes had all the power. It’s only since the last 70 years that the majority has had a say in governance. These lower castes numerically make up the majority of the country. The process is going to be long and really imperfect, but I still have hope. Democracy is the least bad of all the alternatives, and what’s really alarming today is the assault on democracy that we see.

There is hope for India as long as it doesn’t turn into another Turkey, right? Let’s hope it doesn’t.

There are lots of examples of these strongmen. But I still think that India is too large and too varied to be dominated by any one strongman or -woman.

Indira Gandhi tried to do it with the Emergency—I was living in India at the time—and failed miserably. I hope it will fail miserably with Modi, too. I hope he gets thrown out of office, because he’s a lousy leader and the most long-term damage he’s doing is alienating the country’s Muslims. Every Indian—Hindu or Muslim or Christian—should be alarmed at the direction our country is taking.

You write, “The state insists that you belong to a nation, but I’d rather belong to a community.” What do you mean by that? Is this informed by your Indian background?

Where do I belong? I

belong in Greenwich Village where I live in New York; I belong to Jackson Heights in Queens, where I’ve lived for a long time. I belong in Iowa City. I belong in Nepean Sea Road in Bombay where I grew up, in Bandra where I now go. In Calcutta, where I was born, in Paris, in London, in Sao Paulo, Brazil, in groups of family and friends. This is where I belong. When I go there, I feel at home. It’s global. So, people like us who have two homes, who might go back to our family home in Hyderabad or wherever when we go for holidays, that is home. Then whatever suburb of Atlanta we live in, that is also home. We don’t need to choose. Our home, in the end, as human beings, is a palace. It’s called Planet Earth. We have the God-given right to move all over the earth. These borders, these boundaries—let’s not ever make the mistake of thinking that there is something natural or inevitable about them—have only existed for around 100 years.

And the same thing can be said about having multiple identities, right? You’re a Hindu but you’re also an American.

Exactly. I’ve got a strong Indian accent. I love to eat my dal-bhaat with my hands for lunch, and I love to eat pasta with a fork in the evening. What is my identity? It’s both of them. When I left India, I didn’t lose my

Indianness. I added to it, got enriched by all these

other identities.

Finally, is that what gives you hope? Because you say you have an upbeat message. It’s a dark subject, but at the same time you see hope.

That is one reason, but among the immediate reasons I see hope is—in 2016, that horrible year when Trump got elected, my brother-in-law, Jay Chaudhuri, said he was going to run for state senate. I said, in the South? Are you crazy? It was his first ever run for office. Because he was family, we all went down. We knocked on 10,000 doors. The whole campaign together knocked on 14,000 doors. He was running against

a white opponent in a district that was 90 percent white. He won in a landslide, and he’s now the Democratic whip that is second only to the Democratic

leader in the state senate. The first Indian-American state senator in North Carolina.

And you know why he won? Because he went to all these white people and spoke to them about what matters, which is school funding and the mess Republicans were making of the budget. They didn’t care that he was brown. They couldn’t even pronounce his last name! He had to train his own campaign staff to pronounce his last name. And he’s sitting there, fighting the good fight, a progressive Democrat in the South, an Indian-American. I saw it first-hand. That gives me enormous hope for democracy and this country. That’s why I urge every Indian-American who’s reading this article: think about entering public service, whether it’s volunteering in an NGO or going and volunteering for a political leader. Or better still, running for office.

My mother’s family comes from Nairobi in East Africa and they always held themselves at a distance. They always thought of themselves as not African somehow and many of them were outright racist. We can’t make the same mistake in this country. And I see encouraging signs among the young—they are running for office and winning. And they are also thinking of themselves as desis with a South Asian identity, not just an Indian-American identity. We can undo Partition when we go overseas. We can undo that affliction that the British bestowed on us. We are one people.

Murali Kamma is the managing editor of Khabar. His debut book, Not Native: Short Stories of Immigrant Life in an In-Between World, was published this year by Wising Up Press (www.MuraliKamma.com).

Enjoyed reading Khabar magazine? Subscribe to Khabar and get a full digital copy of this Indian-American community magazine.

blog comments powered by Disqus